1

COMMITTEE PRINT REPORT

" !

117 Congress

2d Session

CP 117–8

PART I

INVESTIGATION OF COMPETITION IN

DIGITAL MARKETS

MAJORITY STAFF REPORT AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

SUBCOMMITTEE ON ANTITRUST,

COMMERCIAL, AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW

OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY OF

THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

PART I

JERROLD NADLER, CHAIR, COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY

DAVID N. CICILLINE, CHAIR, SUBCOMMITTEE ON ANTITRUST,

COMMERCIAL, AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW

ORIGINALLY RELEASED OCTOBER 2020

ADOPTED BY COMMITTEE APRIL 2021

PUBLISHED JULY 2022

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6012 Sfmt 6012 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

C:\Graphics\CONGRESS.#13

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

INVESTIGATION OF COMPETITION IN DIGITAL MARKETS

PART I

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

U

.

S

.

GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE

WASHINGTON

:

1

47–832

COMMITTEE PRINT REPORT

" !

117 Congress

2d Session

CP 117–8

PART I

2022

INVESTIGATION OF COMPETITION IN

DIGITAL MARKETS

MAJORITY STAFF REPORT AND

RECOMMENDATIONS

SUBCOMMITTEE ON ANTITRUST,

COMMERCIAL, AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW

OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY OF

THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

PART I

JERROLD NADLER, CHAIR, COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY

DAVID N. CICILLINE, CHAIR, SUBCOMMITTEE ON ANTITRUST,

COMMERCIAL, AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW

ORIGINALLY RELEASED OCTOBER 2020

ADOPTED BY COMMITTEE APRIL 2021

PUBLISHED JULY 2022

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 5012 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

C:\Graphics\CONGRESS.#13

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

2

MAJORITY STAFF

SUBCOMMITTEE ON ANTITRUST, COMMERCIAL,

AND ADMINISTRATIVE LAW

SLADE BOND

Chief Counsel

LINA KHAN

Counsel

PHILLIP BERENBROICK

Counsel

ANNA LENHART

Technologist

JOSEPH EHRENKRANTZ

Special Assistant

AMANDA LEWIS

Counsel on Detail

MARY HELEN WIMBERLY

Counsel on Detail

JOSEPH VAN WYE

Legislative Aide

CATHERINE LARSEN

Special Assistant

COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY

PERRY APELBAUM

Staff Director and Chief

Counsel

AARON HILLER

Deputy Chief Counsel

SHADAWN REDDICK-

SMITH

Communications

Director

JESSICA PRESLEY

Director of Digital

Strategy

MADELINE STRASSER

Chief Clerk

AMY RUTKIN

Chief of Staff

JOHN WILLIAMS

Parliamentarian

DANIEL SCHWARZ

Director of Strategic

Communications

MOH SHARMA

Director of Member

Services and Outreach

& Policy Advisor

JOHN DOTY

Senior Advisor

DAVID GREENGRASS

Senior Counsel

ARYA HARIHARAN

Deputy Chief Oversight

Counsel

MATTHEW ROBINSON

Counsel

KAYLA HAMEDI

Deputy Press Secretary

NATHAN ADAL

Legal Fellow

KARNA ADAM

Legal Fellow

WILLIAM BEKKER

Legal Fellow

KYLE BIGLEY

Legal Fellow

MICHAEL ENSEKI-

FRANK

Legal Fellow

BENJAMIN FEIS

Legal Fellow

CORY GORDON

Legal Fellow

ETHAN GURWITZ

Legal Fellow

DOMENIC POWELL

Legal Fellow

ARMAN RAMNATH

Legal Fellow

REED SHOWALTER

Legal Fellow

JO

¨

EL THOMPSON

Legal Fellow

KURT WALTERS

Legal Fellow

KRYSTALYN WEAVER

Legal Fellow

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5012 Sfmt 6602 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

(III)

CONTENTS

PART I

I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 1

A. Chairs’ Foreword ............................................................................................. 1

B. Executive Summary ........................................................................................ 4

1. Subcommittee’s Investigation ...................................................................... 4

2. Findings ........................................................................................................ 5

3. Recommendations ......................................................................................... 13

II. THE INVESTIGATION OF COMPETITION IN DIGITAL MARKETS ........ 14

A. Requests for Information and Submissions ................................................... 14

1. First-Party Requests for Information ......................................................... 14

2. Process for Obtaining Responses to First-Party Requests ........................ 18

3. Third-Party Requests for Information ........................................................ 18

4. Antitrust Agencies Requests for Information ............................................ 20

B. Hearings ........................................................................................................... 21

C. Roundtables ..................................................................................................... 23

D. Prior Investigations ........................................................................................ 24

III. BACKGROUND ................................................................................................ 27

A. Overview of Competition in Digital Markets ................................................ 27

1. The Role of Competition Online .................................................................. 27

2. Market Structure .......................................................................................... 28

3. Barriers to Entry .......................................................................................... 30

B. Effects of Platform Market Power .................................................................. 35

1. Innovation and Entrepreneurship .............................................................. 35

2. Privacy and Data Protection ....................................................................... 39

3. The Free and Diverse Press ........................................................................ 44

4. Political and Economic Liberty ................................................................... 58

IV. MARKETS INVESTIGATED ............................................................................ 61

A. Online Search .................................................................................................. 61

B. Online Commerce ............................................................................................ 68

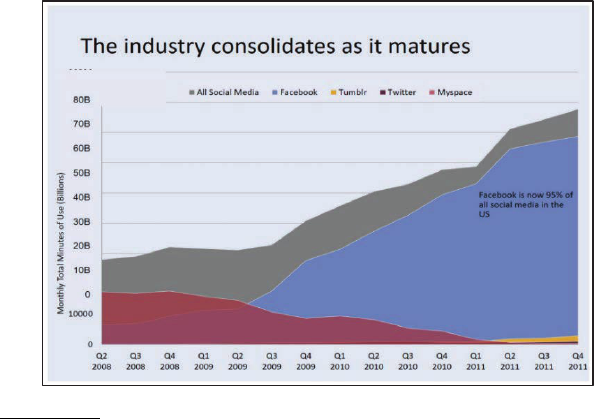

C. Social Networks and Social Media ................................................................. 71

1. Social Networks Are Distinguishable from Social Media ......................... 73

2. Market Concentration .................................................................................. 74

D. Mobile App Stores ........................................................................................... 75

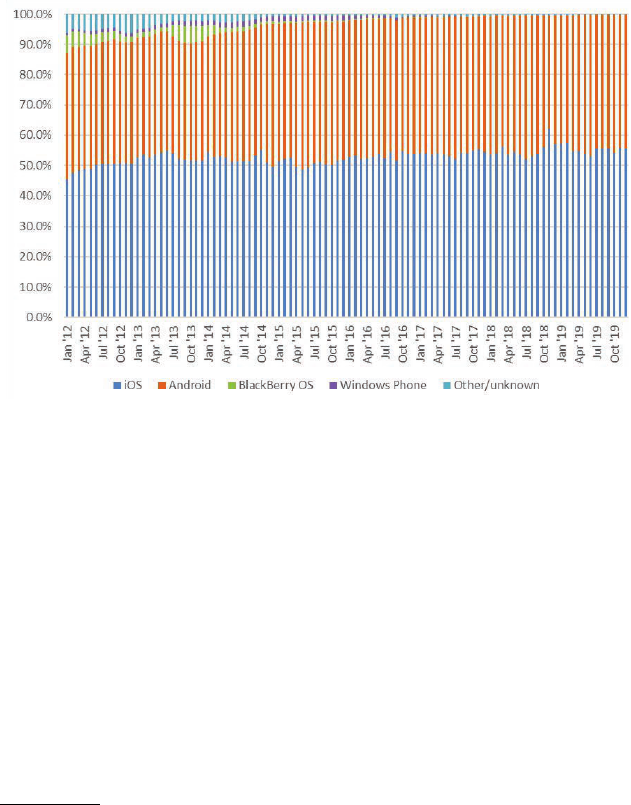

E. Mobile Operating Systems .............................................................................. 82

F. Digital Mapping ............................................................................................... 88

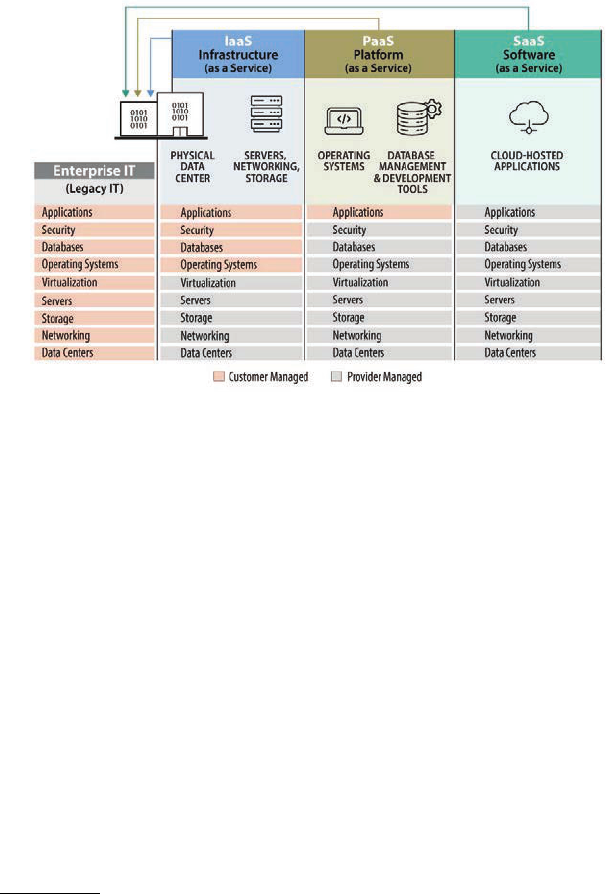

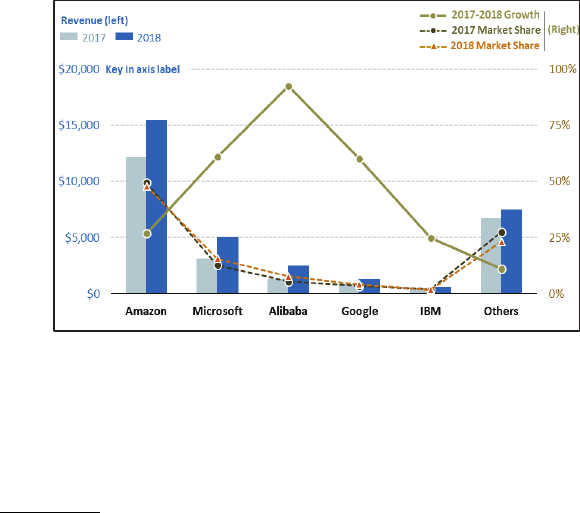

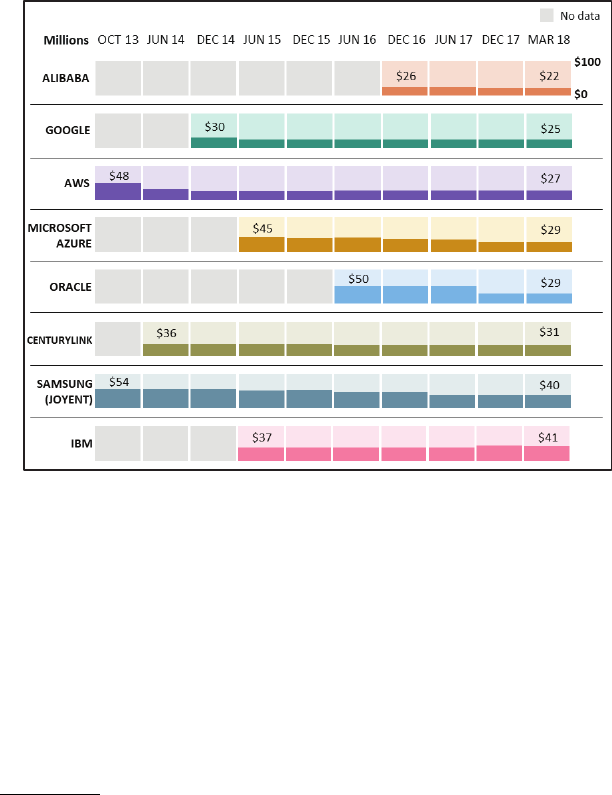

G. Cloud Computing ............................................................................................ 91

H. Voice Assistant ................................................................................................ 100

I. Web Browsers ................................................................................................... 105

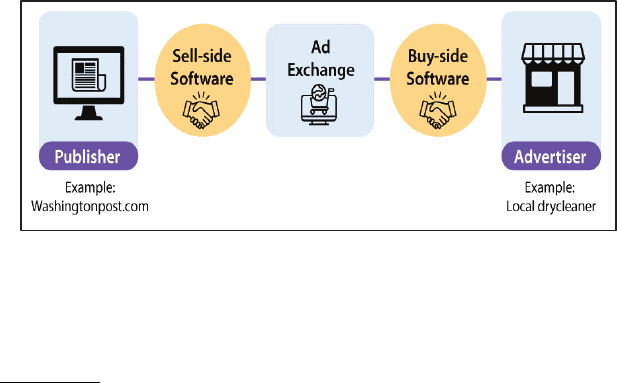

J. Digital Advertising ........................................................................................... 107

V. DOMINANT ONLINE PLATFORMS ................................................................ 110

A. Facebook ........................................................................................................... 110

1. Overview ....................................................................................................... 110

2. Social Networking ........................................................................................ 111

3. Digital Advertising ....................................................................................... 141

B. Google ............................................................................................................... 144

1. Overview ....................................................................................................... 144

2. Search ............................................................................................................ 146

3. Digital Advertisements ................................................................................ 173

4. Android and Google Play Store ................................................................... 177

5. Chrome .......................................................................................................... 186

6. Maps .............................................................................................................. 193

7. Cloud ............................................................................................................. 205

C. Amazon ............................................................................................................. 207

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00005 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

Page

C. Amazon—Continued

1. Overview ....................................................................................................... 207

2. Amazon.com .................................................................................................. 212

3. Fulfillment and Delivery ............................................................................. 254

4. Alexa’s Internet of Things Ecosystem ......................................................... 256

5. Amazon Web Services .................................................................................. 265

D. Apple ................................................................................................................ 277

1. Overview ....................................................................................................... 277

2. iOS and the App Store ................................................................................. 281

3. Siri Intelligent Voice Assistant ................................................................... 314

VI. RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................................... 317

A. Restoring Competition in the Digital Economy ............................................ 318

1. Reduce Conflicts of Interest Through Structural Separations and Line

of Business Restrictions ............................................................................... 319

2. Implement Rules to Prevent Discrimination, Favoritism, and Self-

Preferencing .................................................................................................. 322

3. Promote Innovation Through Interoperability and Open Access ............. 324

4. Reduce Market Power Through Merger Presumptions ............................. 326

5. Create an Even Playing Field for the Free and Diverse Press ................ 328

6. Prohibit Abuse of Superior Bargaining Power and Require Due Proc-

ess ................................................................................................................... 329

B. Strengthening the Antitrust Laws ................................................................. 330

1. Restore the Antimonopoly Goals of the Antitrust Laws ........................... 330

2. Invigorate Merger Enforcement .................................................................. 331

3. Rehabilitate Monopolization Law ............................................................... 334

4. Additional Measures to Strengthen the Antitrust Laws ........................... 337

C. Strengthening Antitrust Enforcement ........................................................... 337

1. Congressional Oversight .............................................................................. 337

2. Agency Enforcement ..................................................................................... 339

3. Private Enforcement .................................................................................... 341

VII. APPENDIX: MERGERS AND ACQUISITIONS BY DOMINANT PLAT-

FORMS ................................................................................................................. 343

A. Amazon ............................................................................................................. 344

B. Apple ................................................................................................................ 346

C. Facebook ........................................................................................................... 349

D. Google ............................................................................................................... 351

VIII. APPENDIX: ADDITIONAL VIEWS OF MEMBERS OF JUDICIARY

COMMITTEE ....................................................................................................... 357

A. The Honorable Eric Swalwell ......................................................................... 358

B. The Honorable Zoe Lofgren ............................................................................ 359

C. The Honorable Jim Jordan ............................................................................. 362

PART II

IX. APPENDIX: TRANSCRIPTS OF HEARINGS IN ‘‘ONLINE PLATFORMS

AND MARKET POWER’’ SERIES

A. Online Platforms and Market Power, Part 1: The Free and Diverse

Press .................................................................................................................. 367

B. Online Platforms and Market Power, Part 2: Innovation and Entrepre-

neurship ............................................................................................................ 589

C. Online Platforms and Market Power, Part 3: The Role of Data and

Privacy in Competition ..................................................................................... 1204

D. Online Platforms and Market Power, Part 4: Perspectives of the Anti-

trust Agencies ................................................................................................... 1419

PART III

E. Online Platforms and Market Power, Part 5: Competitors in the Digital

Economy ............................................................................................................ 1573

F. Online Platforms and Market Power, Part 6: Examining the Dominance

of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google ....................................................... 1709

G. Proposals to Strengthen the Antitrust Laws and Restore Competition

Online ................................................................................................................ 2695

VerDate Sep 11 2014 17:56 Jul 05, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00006 Fmt 5904 Sfmt 5904 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

(1)

I. INTRODUCTION

A. Chairs’ Foreword

In June 2019, the Committee on the Judiciary initiated a bipar-

tisan investigation into the state of competition online, spear-

headed by the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Ad-

ministrative Law. As part of a top-to-bottom review of the market,

the Subcommittee examined the dominance of Amazon, Apple,

Facebook, and Google, and their business practices to determine

how their power affects our economy and our democracy. Addition-

ally, the Subcommittee performed a review of existing antitrust

laws, competition policies, and current enforcement levels to assess

whether they are adequate to address market power and anti-

competitive conduct in digital markets.

Over the course of our investigation, we collected extensive evi-

dence from these companies as well as from third parties—totaling

nearly 1.3 million documents. We held seven hearings to review the

effects of market power online—including on the free and diverse

press, innovation, and privacy—and a final hearing to examine po-

tential solutions to concerns identified during the investigation and

to inform this Report’s recommendations.

A year after initiating the investigation, we received testimony

from the Chief Executive Officers of the investigated companies:

Jeff Bezos, Tim Cook, Mark Zuckerberg, and Sundar Pichai. For

nearly six hours, we pressed for answers about their business prac-

tices, including about evidence concerning the extent to which they

have exploited, entrenched, and expanded their power over digital

markets in anticompetitive and abusive ways. Their answers were

often evasive and non-responsive, raising fresh questions about

whether they believe they are beyond the reach of democratic over-

sight.

Although these four corporations differ in important ways, study-

ing their business practices has revealed common problems. First,

each platform now serves as a gatekeeper over a key channel of

distribution. By controlling access to markets, these giants can pick

winners and losers throughout our economy. They not only wield

tremendous power, but they also abuse it by charging exorbitant

fees, imposing oppressive contract terms, and extracting valuable

data from the people and businesses that rely on them. Second,

each platform uses its gatekeeper position to maintain its market

power. By controlling the infrastructure of the digital age, they

have surveilled other businesses to identify potential rivals, and

have ultimately bought out, copied, or cut off their competitive

threats. And, finally, these firms have abused their role as inter-

mediaries to further entrench and expand their dominance. Wheth-

er through self-preferencing, predatory pricing, or exclusionary con-

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00007 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

2

duct, the dominant platforms have exploited their power in order

to become even more dominant.

To put it simply, companies that once were scrappy, underdog

startups that challenged the status quo have become the kinds of

monopolies we last saw in the era of oil barons and railroad ty-

coons. Although these firms have delivered clear benefits to society,

the dominance of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google has come

at a price. These firms typically run the marketplace while also

competing in it—a position that enables them to write one set of

rules for others, while they play by another, or to engage in a form

of their own private quasi regulation that is unaccountable to any-

one but themselves.

The effects of this significant and durable market power are cost-

ly. The Subcommittee’s series of hearings produced significant evi-

dence that these firms wield their dominance in ways that erode

entrepreneurship, degrade Americans’ privacy online, and under-

mine the vibrancy of the free and diverse press. The result is less

innovation, fewer choices for consumers, and a weakened democ-

racy.

Nearly a century ago, Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis

wrote: ‘‘We must make our choice. We may have democracy, or we

may have wealth concentrated in the hands of a few, but we cannot

have both.’’ Those words speak to us with great urgency today.

Although we do not expect that all of our Members will agree on

every finding and recommendation identified in this Report, we

firmly believe that the totality of the evidence produced during this

investigation demonstrates the pressing need for legislative action

and reform. These firms have too much power, and that power

must be reined in and subject to appropriate oversight and enforce-

ment. Our economy and democracy are at stake.

As a charter of economic liberty, the antitrust laws are the back-

bone of open and fair markets. When confronted by powerful mo-

nopolies over the past century—be it the railroad tycoons and oil

barons or Ma Bell and Microsoft—Congress has acted to ensure

that no dominant firm captures and holds undue control over our

economy or our democracy. We face similar challenges today. Con-

gress—not the courts, agencies, or private companies—enacted the

antitrust laws, and Congress must lead the path forward to mod-

ernize them for the economy of today, as well as tomorrow. Our

laws must be updated to ensure that our economy remains vibrant

and open in the digital age.

Congress must also ensure that the antitrust agencies aggres-

sively and fairly enforce the law. Over the course of the investiga-

tion, the Subcommittee uncovered evidence that the antitrust agen-

cies failed, at key occasions, to stop monopolists from rolling up

their competitors and failed to protect the American people from

abuses of monopoly power. Forceful agency action is critical.

Lastly, Congress must revive its tradition of robust oversight

over the antitrust laws and increased market concentration in our

economy. In prior Congresses, the Subcommittee routinely exam-

ined these concerns in accordance with its constitutional mandate

to conduct oversight and perform its legislative duties. As a 1950

report from the then-named Subcommittee on the Study of Monop-

oly Power described its mandate: ‘‘It is the province of this sub-

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00008 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

3

1

H. R

EP

. N

O

. 82–255, at 2 (1951) (Aluminum: Report of the Subcomm. on Study of Monopoly

Power of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary).

committee to investigate factors which tend to eliminate competi-

tion, strengthen monopolies, injure small business, or promote

undue concentration of economic power; to ascertain the facts, and

to make recommendations based on those findings.’’

1

Similarly, the Subcommittee has followed the facts before it to

produce this Report, which is the product of a considerable evi-

dentiary and oversight record. This record includes: 1,287,997 docu-

ments and communications; testimony from 38 witnesses; a hear-

ing record that spans more than 1,800 pages; 38 submissions from

60 antitrust experts from across the political spectrum; and inter-

views with more than 240 market participants, former employees

of the investigated platforms, and other individuals totaling thou-

sands of hours. The Subcommittee has also held hearings and

roundtables with industry and government witnesses, consultations

with subject-matter experts, and a careful—and at times pains-

taking—review of large volumes of evidence provided by industry

participants and regulators.

In light of these efforts, we extend our deep gratitude to the staff

of the Subcommittee and Full Committee for their diligent work in

this regard, particularly during the COVID–19 pandemic and other

challenging circumstances over the past year.

Finally, as an institutional matter, we close by noting that the

Committee’s requests for information from agencies and any non-

public briefings were solely for the purpose of carrying out our con-

stitutionally based legislative and oversight functions. In par-

ticular, the information requested was vital to informing our as-

sessment of whether existing antitrust laws are adequate for tack-

ling current competition problems, as well as in uncovering poten-

tial reasons for under-enforcement. The Report is based on the doc-

uments and information collected during its investigation, and the

Committee fully respects the separate and independent decisional

processes employed by enforcement authorities with respect to such

matters.

Although the companies provided substantial information and

numerous documents to the Subcommittee, they declined to

produce certain critical information and crucial documents we re-

quested. The material withheld was identified by the Committee as

relevant to the investigation and included, primarily, two cat-

egories of information: (1) documents the companies claimed were

protected by common law privileges; and (2) documents that were

produced to antitrust authorities in ongoing investigations, or that

related to the subject matter of these ongoing investigations.

Institutionally, we reject any argument that the mere existence

of ongoing litigation prevents or prohibits Congress from obtaining

information relevant to its legislative and oversight prerogatives.

We strongly disagree with the assertion that any requests for such

materials and any compliance with those requests interfere with

the decisional processes in ongoing investigations. Furthermore,

while Congress is fully subject to constitutional protections, we can-

not agree that we are bound by common law privileges as asserted

by the companies. While we determined that insufficient time ex-

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00009 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

4

2

Press Release, H. Comm. on the Judiciary, House Judiciary Committee Launches Bipartisan

Investigation into Competition in Digital Markets (June 3, 2019), https://judiciary.house.gov/

news/press-releases/house-judiciary-committee-launches-bipartisan-investigation-competition-

digital.

3

We extend our sincere thanks to Peter Karafotas, Rich Luchette, and Francis Grubar, in

the Office of Congressman David N. Cicilline, for their relentless work and selfless devotion

throughout the investigation. We would also like to recognize the following staff for their signifi-

cant contributions during the investigation: Dick Meltzer, Michael Tecklenburg, Kenneth

DeGraff, and Victoria Houed in the Office of the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives;

Daniel Flores, former Minority Chief Counsel, Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Ad-

ministrative Law; Danny Johnson, former Minority Counsel, Committee on the Judiciary; Jacqui

Kappler, Legislative Director, the Honorable Henry ‘‘Hank’’ Johnson, Jr.; Devon Ombres, Legis-

lative Counsel, the Honorable Jamie Raskin; Elly Kugler, Senior Counsel, the Honorable

Pramila Jayapal; Jennifer Chan, Legislative Director, the Honorable Pramila Jayapal; Stuart

Styron, Senior Legislative Assistant, the Honorable Val Demings; Keanu Rivera, Legislative As-

sistant, the Honorable Mary Gay Scanlon; Lindsey Garber, Legislative Counsel, the Honorable

Joe Neguse; Miya Patel, former Legislative Assistant, the Honorable Joe Neguse; and Natalie

Knight, Legislative Counsel, the Honorable Lucy McBath. Staff would also like to thank Mat-

thew Bisenius in the Office of Congressman F. James Sensenbrenner, as well as Garrett Ventry

in the Office of Congressman Ken Buck, for their commitment to bipartisan cooperation. We also

thank Hillary Marston, Legal Intern for the Committee on the Judiciary, for her assistance. Fi-

nally, we thank Clare Cho and Mari Lee at the Congressional Research Service for their sup-

port, as well as graphics and data visualization used within this Report.

4

Press Release, H. Comm. on the Judiciary, House Judiciary Committee Launches Bipartisan

Investigation into Competition in Digital Markets (June 3, 2019), https://judiciary.house.gov/

news/press-releases/house-judiciary-committee-launches-bipartisan-investigation-competition-

digital.

5

See, e.g., Meehreen Khan, EU Targets Tech Giants over Unfair Business Practices, F

IN

.

T

IMES

(Apr. 25, 2018), https://www.ft.com/content/d7228bec-4879-11e8-8ee8-cae73aab7ccb;

Adam Satariano, Google Is Fined $57 Million Under Europe’s Data Privacy Law, N.Y. T

IMES

(Jan. 21, 2019), https://www.nytimes.com/2019/01/21/technology/google-europe-gdpr-fine.

html; Richard Waters et al., Global Regulators’ Net Tightens Around Big Tech, F

IN

. T

IMES

(June

5, 2019), https://www.ft.com/content/973f8b36-86f0-11e9-97ea-05ac2431f453.

ists to pursue these additional materials during this Congress, the

Committee expressly reserves the right to invoke other available

options, including compulsory process, to obtain the requested in-

formation in the future.

B. Executive Summary

1. Subcommittee’s Investigation

On June 3, 2019, the House Judiciary Committee announced a

bipartisan investigation into competition in digital markets,

2

led by

the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Commercial, and Administrative

Law.

3

The purpose of the investigation was to: (1) document com-

petition problems in digital markets; (2) examine whether domi-

nant firms are engaging in anticompetitive conduct; and (3) assess

whether existing antitrust laws, competition policies, and current

enforcement levels are adequate to address these issues.

4

The Com-

mittee initiated the investigation in response to broad-ranging in-

vestigative reporting, and activity by policymakers and enforcers,

that raised serious concerns about the platforms’ incentives and

ability to harm the competitive process.

5

As part of the investigation, the Subcommittee held seven over-

sight hearings that provided Members of the Subcommittee with an

opportunity to examine the state of competition in digital markets

and the adequacy of existing antitrust laws. A diverse group of wit-

nesses offered testimony on topics related to the effects of market

power on the free and diverse press, on innovation, and on privacy.

Other witnesses who testified included executives from businesses

with concerns about the dominance of the investigated firms. The

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00010 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

5

hearings also provided an opportunity for key executives from

Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple—including the Chief Execu-

tive Officers of these firms—to address evidence that was uncov-

ered during the investigation in a public-facing venue. After each

of the hearings, Members of the Subcommittee submitted questions

for the record (QFRs) to the witnesses.

The Committee requested information from the dominant plat-

forms, from market participants, from the Federal antitrust agen-

cies, and from other relevant parties, for the purpose of obtaining

information that was not otherwise publicly available but was im-

portant to assembling a comprehensive record. The Committee also

sent requests for submissions to various experts in the field, includ-

ing academics, representatives of public interest groups, and prac-

ticing antitrust lawyers. The responses to these requests were in-

dispensable to staff’s ability to complete this Report and its rec-

ommendations for congressional oversight of the antitrust agencies

and legislative action.

This Report is intended to provide policymakers, antitrust enforc-

ers, market participants, and the public with a comprehensive un-

derstanding of the state of competition in the online marketplace.

The Report also provides recommendations for areas of legislative

activity to address the rise and abuse of market power in the dig-

ital economy, as well as areas that warrant additional congres-

sional attention.

2. Findings

(a) Overview. The open internet has delivered significant benefits

to Americans and the U.S. economy. Over the past few decades, it

has created a surge of economic opportunity, capital investment,

and pathways for education. The COVID–19 pandemic has under-

scored the importance of internet access that is affordable, competi-

tive, and widely available for workers, families, and businesses.

The online platforms investigated by the Subcommittee—Ama-

zon, Apple, Facebook, and Google—also play an important role in

our economy and society as the underlying infrastructure for the

exchange of communications, information, and goods and services.

As of September 2020, the combined valuation of these platforms

is more than $5 trillion—more than a third of the value of the S&P

100. As we continue to shift our work, commerce, and communica-

tions online, these firms stand to become even more interwoven

into the fabric of our economy and our lives.

Over the past decade, the digital economy has become highly con-

centrated and prone to monopolization. Several markets inves-

tigated by the Subcommittee—such as social networking, general

online search, and online advertising—are dominated by just one

or two firms. The companies investigated by the Subcommittee—

Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google—have captured control over

key channels of distribution and have come to function as gate-

keepers. Just a decade into the future, 30 percent of the world’s

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00011 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

6

6

Catherine Fong et al., Prime Day and the Broad Reach of Amazon’s Ecosystem, M

C

K

INSEY

&

C

O

. (Aug. 2, 2019), https://www.mckinsey.com/business-functions/marketing-and-sales/our-

insights/prime-day-and-the-broad-reach-of-amazons-ecosystem (‘‘This ecosystem strategy in par-

ticular has significant competitive implications because McKinsey estimates that in ten years,

30 percent of the world’s gross economic output will be from companies that operate a network

of interconnected businesses, such as those run by Amazon, Alibaba, Google, and Facebook.’’).

7

Colleen Cunningham, Florian Ederer & Song Ma, Killer Acquisitions 1 (Yale Sch. of Mgmt.,

Working Paper, Mar. 2019), https://perma.cc/L6YL-YL8K (describing the practice of

‘‘acquir[ing] innovative targets solely to discontinue the target’s innovative projects and preempt

future competition’’). See also C. Scott Hemphill & Tim Wu, Nascent Competitors, 168 U. P

A

.

L. R

EV

. 1879, 1880 (2020), https://perma.cc/62HH-34ZL (‘‘A nascent competitor is a firm whose

prospective innovation represents a serious future threat to an incumbent.’’).

8

See infra Section V.

gross economic output may lie with these firms, and just a handful

of others.

6

In interviews with the Subcommittee, numerous businesses de-

scribed how dominant platforms exploit their gatekeeper power to

dictate terms and extract concessions that no one would reasonably

consent to in a competitive market. Market participants indicated

that their dependence on these gatekeepers to access users and

markets requires concessions and demands that carry significant

economic harm, but that are ‘‘the cost of doing business’’ given the

lack of options.

This significant and durable market power is due to several fac-

tors, including a high volume of acquisitions by the dominant plat-

forms. Together, the firms investigated by the Subcommittee have

acquired hundreds of companies just in the last ten years. In some

cases, a dominant firm evidently acquired nascent or potential com-

petitors to neutralize a competitive threat or to maintain and ex-

pand the firm’s dominance. In other cases, a dominant firm ac-

quired smaller companies to shut them down or discontinue under-

lying products entirely—transactions aptly described as ‘‘killer ac-

quisitions.’’

7

In the overwhelming number of cases, the antitrust agencies did

not request additional information and documentary material

under their pre-merger review authority in the Clayton Act to ex-

amine whether the proposed acquisition may substantially lessen

competition or tend to create a monopoly if allowed to proceed as

proposed. For example, of Facebook’s nearly 100 acquisitions, the

Federal Trade Commission (FTC) engaged in an extensive inves-

tigation of just one acquisition: Facebook’s purchase of Instagram

in 2012.

During the investigation, the Subcommittee found evidence of

monopolization and monopoly power. For example, the strong net-

work effects associated with Facebook has tipped the market to-

ward monopoly such that Facebook competes more vigorously

among its own products—Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp, and

Messenger—than with actual competitors.

As demonstrated during a series of hearings held by the Sub-

committee and as detailed in this Report,

8

the online platforms’

dominance carries significant costs. It has diminished consumer

choice, eroded innovation and entrepreneurship in the U.S. econ-

omy, weakened the vibrancy of the free and diverse press, and un-

dermined Americans’ privacy.

These concerns are shared by the majority of Americans. On Sep-

tember 24, 2020, Consumer Reports (CR) published a survey titled

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00012 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

7

9

C

ONSUMER

. R

EPS

., P

LATFORM

P

ERCEPTIONS

: C

ONSUMER

A

TTITUDES ON

C

OMPETITION AND

F

AIRNESS IN

O

NLINE

P

LATFORMS

(2020), https://advocacy.consumerreports.org/wp-content/

uploads/2020/09/FINAL-CR-survey-report.platform-perceptions-consumer-attitudes-.september-

2020.pdf.

10

Id.

11

Submission from Facebook, to H. Comm. on the Judiciary, FB–HJC–ACAL–00045388 (Feb.

18, 2014), https://judiciary.house.gov/uploadedfiles/0004538800045389.pdf (‘‘[W]e are going to

spend 5–10% of our market cap every couple years to shore up our position . . . I hate the word

‘land grab’ but I think that is the best convincing argument and we should own that.’’).

12

Id. at FB–HJC–ACAL–00067600 (Apr. 9, 2012), https://judiciary.house.gov/uploadedfiles/

0006760000067601.pdf.

13

Id.

14

Id. at FB–HJC–ACAL–00049006 (Apr. 18, 2012) (on file with Comm.) (‘‘Network effects

make it very difficult to compete with us—In every country we’ve tipped we are still winning.’’).

15

Id.

16

Id. at FB–HJC–ACAL–00111406 (Oct. 2018) [hereinafter Cunningham Memo] (‘‘Facebook

has high reach and time-spent in most countries. User growth is tracking internet growth: glob-

al reach is roughly stable.’’).

17

Id.

18

Id. at 11.

‘‘Platform Perceptions: Consumer Attitudes on Competition and

Fairness in Online Platforms.’’

9

Among its findings:

• Eighty-five percent of Americans are concerned—either very concerned or

somewhat concerned—about the amount of data online platforms store about

them, and eighty-one percent are concerned that platforms are collecting and

holding this data in order to build out more comprehensive consumer profiles.

• Fifty-eight percent are not confident that they are getting objective and unbi-

ased search results when using an online platform to shop or search for infor-

mation.

• Seventy-nine percent say Big Tech mergers and acquisitions unfairly under-

mine competition and consumer choice.

10

• Sixty percent support more government regulation of online platforms, includ-

ing mandatory interoperability features, to make it easier for users to switch

from one platform to another without losing important data or connections.

(b) Facebook. Facebook has monopoly power in the market for so-

cial networking. Internal communications among the company’s

Chief Executive Officer, Mark Zuckerberg, and other senior execu-

tives indicate that Facebook acquired its competitive threats to

maintain and expand its dominance. For example, a senior execu-

tive at the company described its acquisition strategy as a ‘‘land

grab’’ to ‘‘shore up’’ Facebook’s position,

11

while Facebook’s CEO

said that Facebook ‘‘can likely always just buy any competitive

startups,’’

12

and agreed with one of the company’s senior engineers

that Instagram was a threat to Facebook.

13

Facebook’s monopoly power is firmly entrenched and unlikely to

be eroded by competitive pressure from new entrants or existing

firms. In 2012, the company described its network effects as a

‘‘flywheel’’ in an internal presentation prepared for Facebook at the

direction of its Chief Financial Officer.

14

This presentation also

said that Facebook’s network effects get ‘‘stronger every day.’’

15

More recent documents produced during the investigation by

Facebook show that it has tipped the social networking market to-

ward a monopoly, and now considers competition within its own

family of products to be more considerable than competition from

any other firm. These documents include an October 2018 memo-

randum by Thomas Cunningham, a senior data scientist and econo-

mist at Facebook,

16

for Mr. Zuckerberg and Javier Olivan,

Facebook’s Director of Growth.

17

Among other things, the

Cunningham Memo found that the network effects of Facebook and

its family of products as ‘‘very strong’’

18

and that there are strong

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00013 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

8

19

Id. at 9.

20

Id.

21

Interview with Former Instagram Employee (Oct. 2, 2020).

tipping points in the social networking market that create competi-

tion for the market, rather than competition within the market.

19

According to a former senior employee at Instagram who was in-

volved in the preparation of this document for review by Mr.

Zuckerberg and Mr. Olivan, the Cunningham Memo guided

Facebook’s growth strategy, particularly with regard to Insta-

gram.

20

They explained:

The question was how do we position Facebook and Instagram to not compete

with each other. The concern was that Instagram would hit a tipping point ....

There was brutal in-fighting between Instagram and Facebook at the time. It

was very tense. It was back when Kevin Systrom was still at the company. He

wanted Instagram to grow naturally and as widely as possible. But Mark was

clearly saying ‘‘do not compete with us.’’ . . . It was collusion, but within an inter-

nal monopoly. If you own two social media utilities, they should not be allowed

to shore each other up. It’s unclear to me why this should not be illegal. You

can collude by acquiring a company.

21

Facebook has also maintained its monopoly through a series of

anticompetitive business practices. The company used its data ad-

vantage to create superior market intelligence to identify nascent

competitive threats and then acquire, copy, or kill these firms.

Once dominant, Facebook selectively enforced its platform policies

based on whether it perceived other companies as competitive

threats. In doing so, it advantaged its own services while weak-

ening other firms.

In the absence of competition, Facebook’s quality has deterio-

rated over time, resulting in worse privacy protections for its users

and a dramatic rise in misinformation on its platform.

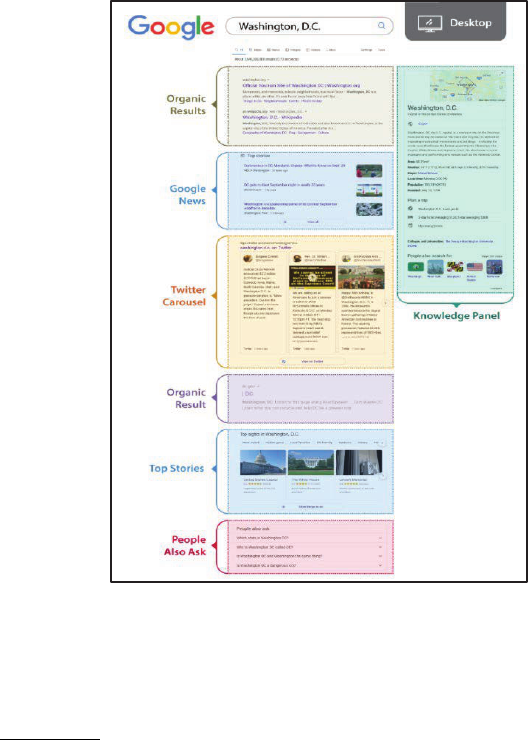

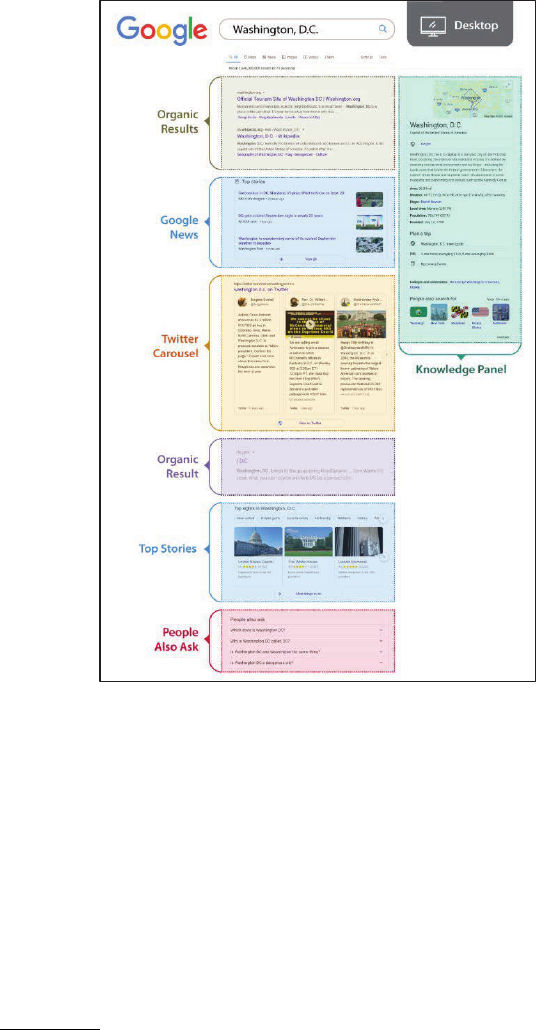

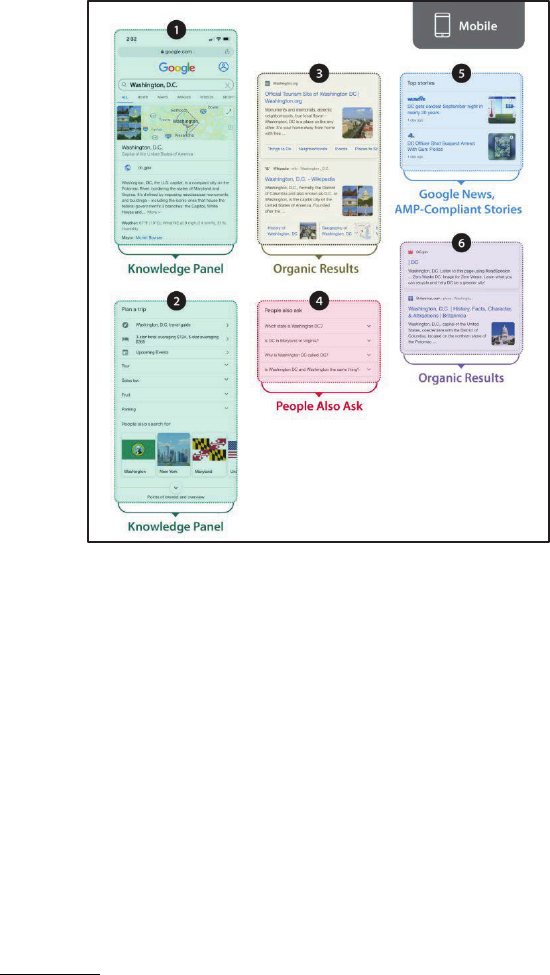

(c) Google. Google has a monopoly in the markets for general on-

line search and search advertising. Google’s dominance is protected

by high entry barriers, including its click-and-query data and the

extensive default positions that Google has obtained across most of

the world’s devices and browsers. A significant number of entities—

spanning major public corporations, small businesses, and entre-

preneurs—depend on Google for traffic, and no alternate search en-

gine serves as a substitute.

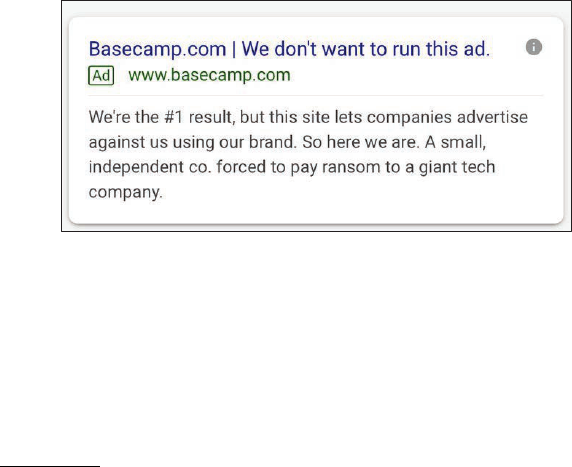

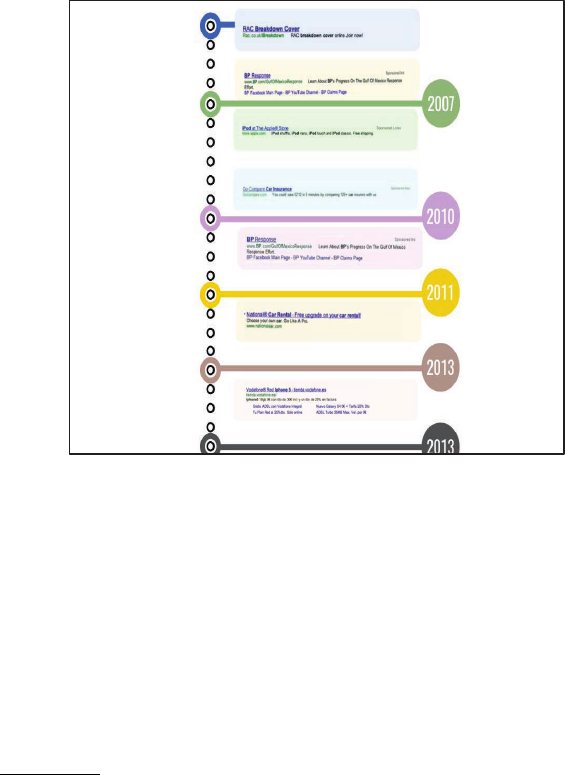

Google maintained its monopoly over general search through a

series of anticompetitive tactics. These include an aggressive cam-

paign to undermine vertical search providers, which Google viewed

as a significant threat. Documents show that Google used its

search monopoly to misappropriate content from third parties and

to boost Google’s own inferior vertical offerings, while imposing

search penalties to demote third-party vertical providers. Since

capturing a monopoly over general search, Google has steadily pro-

liferated its search results page with ads and with Google’s own

content, while also blurring the distinction between paid ads and

organic results. As a result of these tactics, Google appears to be

siphoning off traffic from the rest of the web, while entities seeking

to reach users must pay Google steadily increasing sums for ads.

Numerous market participants analogized Google to a gatekeeper

that is extorting users for access to its critical distribution channel,

even as its search page shows users less relevant results.

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00014 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

9

A second way Google has maintained its monopoly over general

search has been through a series of anticompetitive contracts. After

purchasing the Android operating system in 2005, Google used con-

tractual restrictions and exclusivity provisions to extend Google’s

search monopoly from desktop to mobile. Documents show that

Google required smartphone manufacturers to pre-install and give

default status to Google’s own apps, impeding competitors in search

as well as in other app markets. As search activity now migrates

from mobile to voice, third-party interviews suggest Google is again

looking for ways to maintain its monopoly over search access points

through a similar set of practices.

Since capturing the market for online search, Google has ex-

tended into a variety of other lines of business. Today, Google is

ubiquitous across the digital economy, serving as the infrastructure

for core products and services online. Through Chrome, Google now

owns the world’s most popular browser—a critical gateway to the

internet that it has used to both protect and promote its other lines

of business. Through Google Maps, Google now captures over eight

percent of the market for navigation mapping services—a key input

over which Google consolidated control through an anticompetitive

acquisition and which it now leverages to advance its position in

search and advertising. And through Google Cloud, Google has an-

other core platform in which it is now heavily investing through ac-

quisitions, positioning itself to dominate the ‘‘Internet of Things,’’

the next wave of surveillance technologies.

Internal communications also reveal that Google exploits infor-

mation asymmetries and closely tracks real-time data across mar-

kets, which—given Google’s scale—provide it with near-perfect

market intelligence. In certain instances, Google has covertly set

up programs to more closely track its potential and actual competi-

tors, including through projects like Android Lockbox.

Each of its services provides Google with a trove of user data, re-

inforcing its dominance across markets and driving greater mone-

tization through online ads. Through linking these services to-

gether, Google increasingly functions as an ecosystem of inter-

locking monopolies.

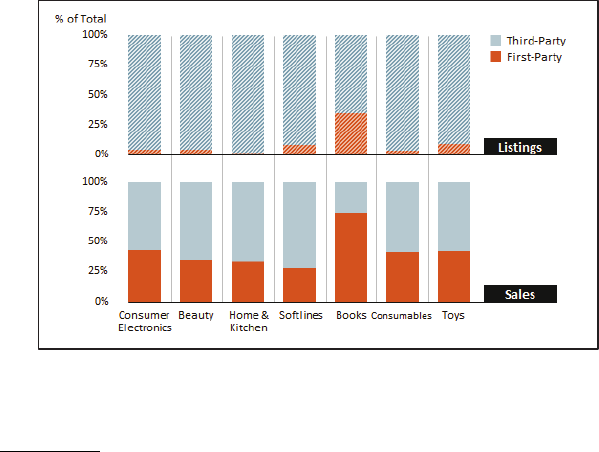

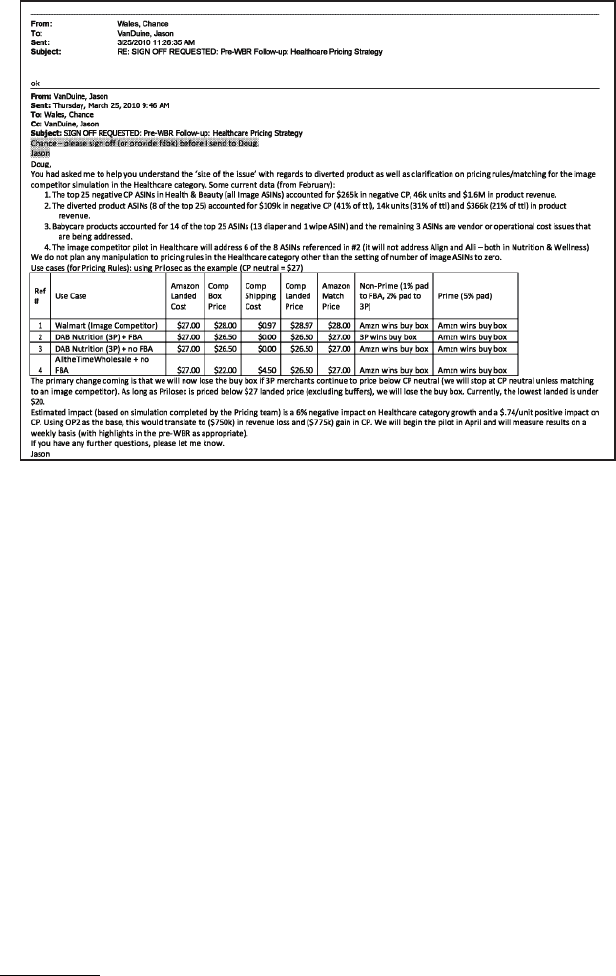

(d) Amazon. Amazon has significant and durable market power

in the U.S. online retail market. This conclusion is based on the

significant record that the Subcommittee collected and reviewed,

including testimonials from third-party sellers, brand manufactur-

ers, publishers, former employees, and other market participants,

as well as Amazon’s internal documents. Although Amazon is fre-

quently described as controlling about forty percent of U.S. online

retail sales, this market share is likely understated, and estimates

of about 50 percent or higher are more credible.

As the dominant marketplace in the United States for online

shopping, Amazon’s market power is at its height in its dealings

with third-party sellers. The platform has monopoly power over

many small- and medium-sized businesses that do not have a via-

ble alternative to Amazon for reaching online consumers. Amazon

has 2.3 million active third-party sellers on its marketplace world-

wide, and a recent survey estimates that about 37 percent of

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00015 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

10

22

J

UNGLE

S

COUT

, T

HE

S

TATE OF THE

A

MAZON

S

ELLER

2020, at 4 (2020), https://www.

junglescout.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/State-of-the-Seller-Survey.pdf.

them—about 850,000 sellers—rely on Amazon as their sole source

of income.

22

Amazon achieved its current dominant position, in part, through

acquiring its competitors, including Diapers.com and Zappos. It has

also acquired companies that operate in adjacent markets, adding

customer data to its stockpile and further shoring up its competi-

tive moats. This strategy has entrenched and expanded Amazon’s

market power in e-commerce, as well as in other markets. The

company’s control over and reach across its many business lines

enable it to self-preference and disadvantage competitors in ways

that undermine free and fair competition. As a result of Amazon’s

dominance, other businesses are frequently beholden to Amazon for

their success.

Amazon has engaged in extensive anticompetitive conduct in its

treatment of third-party sellers. Publicly, Amazon describes third-

party sellers as ‘‘partners.’’ But internal documents show that, be-

hind closed doors, the company refers to them as ‘‘internal competi-

tors.’’ Amazon’s dual role as an operator of its marketplace that

hosts third-party sellers, and a seller in that same marketplace,

creates an inherent conflict of interest. This conflict incentivizes

Amazon to exploit its access to competing sellers’ data and informa-

tion, among other anticompetitive conduct.

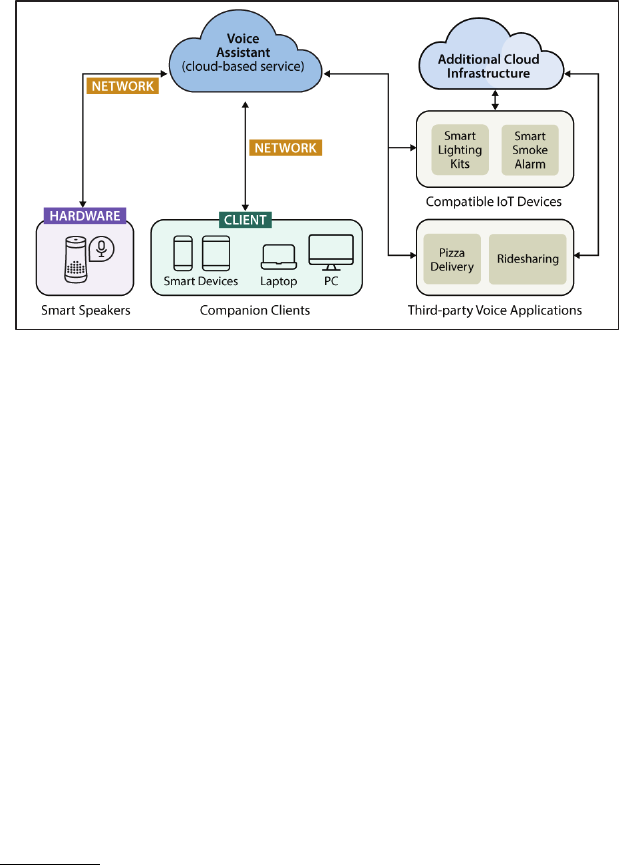

Voice assistant ecosystems are an emerging market with a high

propensity for lock-in and self-preferencing. Amazon has expanded

Alexa’s ecosystem quickly through acquisitions of complementary

and competing technologies, and by selling its Alexa-enabled smart

speakers at deep discounts. The company’s early leadership in this

market is leading to the collection of highly sensitive consumer

data, which Amazon can use to promote its other business, includ-

ing e-commerce and Prime Video.

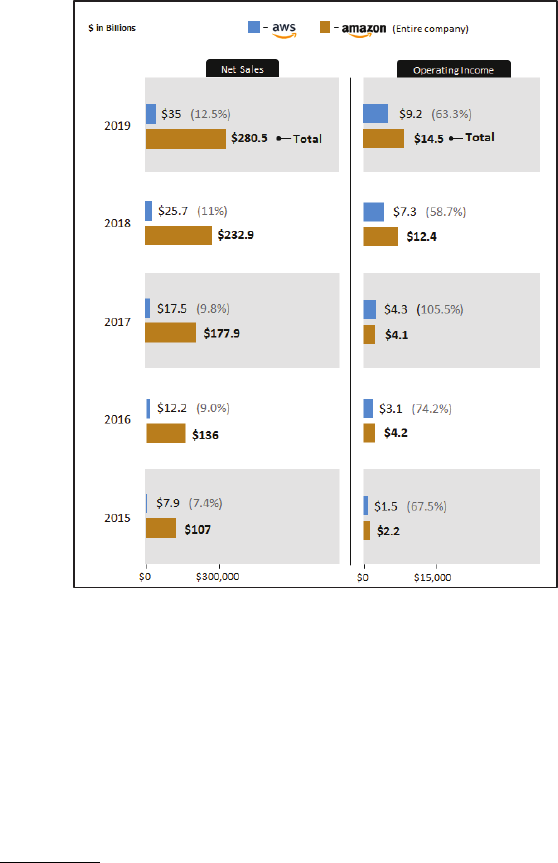

Finally, Amazon Web Services (AWS) provides critical infrastruc-

ture for many businesses with which Amazon competes. This cre-

ates the potential for a conflict of interest where cloud customers

are forced to consider patronizing a competitor, as opposed to se-

lecting the best technology for their business.

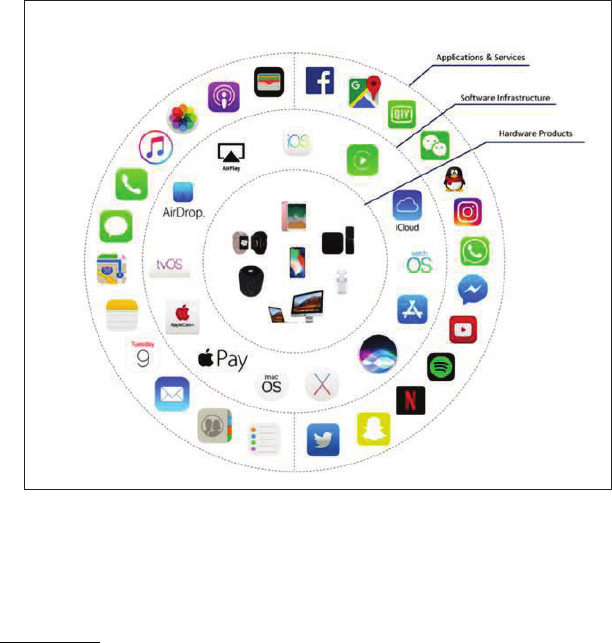

(e) Apple. Apple has significant and durable market power in the

mobile operating system market. Apple’s dominance in this market,

where it controls the iOS mobile operating system that runs on

Apple mobile devices, has enabled it to control all software dis-

tribution to iOS devices. As a result, Apple exerts monopoly power

in the mobile app store market, controlling access to more than 100

million iPhones and iPads in the U.S.

Apple’s mobile ecosystem has produced significant benefits to app

developers and consumers. Launched in 2008, the App Store revo-

lutionized software distribution on mobile devices, reducing bar-

riers to entry for app developers and increasing the choices avail-

able to consumers. Despite this, Apple leverages its control of iOS

and the App Store to create and enforce barriers to competition and

discriminate against and exclude rivals while preferencing its own

offerings. Apple also uses its power to exploit app developers

through misappropriation of competitively sensitive information

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00016 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

11

23

Online Platforms and Market Power, Part 1: The Free and Diverse Press: Hearing Before

the Subcomm. on Antitrust, Commercial and Admin. Law of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary,

116th Cong. 71–73 (2019) [hereinafter Free and Diverse Press Hearing] (statement of David

Pitofsky, Gen. Couns., News Corp).

24

Submission from Source 53, to H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 7 (Oct. 14, 2019) (on file with

Comm.). Although Apple News and Apple News Plus are increasingly popular news aggregators,

most market participants that the Subcommittee received evidence from during the investiga-

tion do not view it as a critical intermediary for online news at this time. Some publishers

raised competition concerns about the tying of payment inside Apple’s news product. Others,

however, did raise concerns about Apple News and Apple News Plus, noting that it is ‘‘not cre-

ating any original journalism itself’’ and competes ‘‘against publishers’ news products . . . for sub-

scription revenues.’’ Id. at 6.

25

Submission from Source 52, to H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 12 (Oct. 30, 2019) (on file with

Comm.).

26

Free and Diverse Press Hearing at 20 (statement of David Chavern, President & CEO,

News Media All.) (‘‘In effect, a couple of dominant tech platforms are acting as regulators of

the digital news industry.’’).

27

Online Platforms and Market Power, Part 2: Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Hearing Be-

fore the Subcomm. on Antitrust, Commercial and Admin. Law of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary,

116th Cong. 76 (2019) [hereinafter Innovation and Entrepreneurship Hearing] (statement of

Timothy Wu, Julius Silver Prof. of Law, Columbia Law Sch.); Online Platforms and Market

Power, Part 3: The of Role of Data and Privacy in Competition: Hearing Before the Subcomm.

on Antitrust, Commercial and Admin. Law of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, 116th Cong. 58–

Continued

and to charge app developers supra-competitive prices within the

App Store. Apple has maintained its dominance due to the pres-

ence of network effects, high barriers to entry, and high switching

costs in the mobile operating system market.

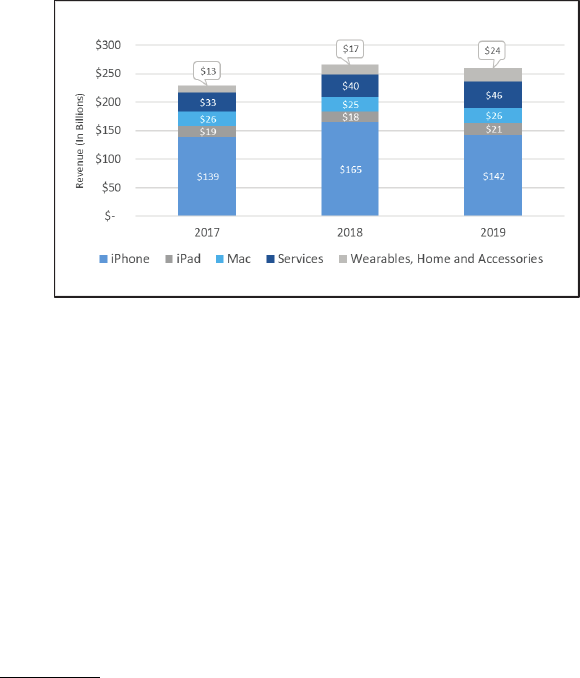

Apple is primarily a hardware company that derives most of its

revenue from sales of devices and accessories. However, as the

market for products like the iPhone has matured, Apple has

pivoted to rely increasingly on sales of its applications and services,

as well as collecting commissions and fees in the App Store. In the

absence of competition, Apple’s monopoly power over software dis-

tribution to iOS devices has resulted in harm to competitors and

competition, reducing quality and innovation among app devel-

opers, and increasing prices and reducing choices for consumers.

(f) Effects of Market Power. The Subcommittee also examined the

effects of market power in digital markets on the free and diverse

press, innovation, privacy and data, and other relevant matters

summarized below for ease of reference.

As part of this process, the Subcommittee received testimony and

submissions showing that the dominance of some online platforms

has contributed to the decline of trustworthy sources of news,

which are essential to our democracy.

23

In several submissions,

news publishers raised concerns about the ‘‘significant and growing

asymmetry of power’’ between dominant platforms and news orga-

nizations, as well as the effect of this dominance on the production

and availability of trustworthy sources of news. Other publishers

said that they are ‘‘increasingly beholden’’ to these firms, and in

particular, to Google and Facebook.

24

Google and Facebook have an

outsized influence over the distribution and monetization of trust-

worthy sources of news online,

25

undermining the quality and

availability of high-quality sources of journalism.

26

This concern is

underscored by the COVID–19 pandemic, which has laid bare the

importance of preserving a vibrant free press in both local and na-

tional markets.

The rise of market power online has also materially weakened in-

novation and entrepreneurship in the U.S. economy.

27

Some ven-

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00017 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

12

60 (2019) [hereinafter Data and Privacy Hearing] (statement of Jason Furman, Prof. of the Prac.

of Econ. Pol’y, Harvard Kennedy Sch.).

28

Raghuram Rajan, Sai Krishna Kamepalli & Luigi Zingales, Kill Zone (Univ. of Chi., Becker

Friedman Inst. for Econ., Working Paper No. 2020–19, Apr. 2020), https://ssrn.com/abstract

=3555915.

29

See generally U.S. Dep’t of Justice Antitrust Div., Public Workshop on Venture Capital and

Antitrust (Feb. 12, 2020) [hereinafter Venture Capital and Antitrust Workshop], https://

www.justice.gov/atr/page/file/1255851/download; C

HI

. B

OOTH

S

TIGLER

C

TR

.

FOR THE

S

TUDY

OF

E

CON

.

&

S

TATE

, S

TIGLER

C

MTE

.

ON

D

IG

. P

LATFORMS

, F

INAL

R

EPORT

, 9 (2019) [herein-

after Stigler Report], https://www.chicagobooth.edu/-/media/research/stigler/pdfs/digital-

platforms---committee-report---stigler-center.pdf.

30

See Interview with Source 146 (May 28, 2020).

31

Howard A. Shelanski, Information, Innovation, and Competition Policy for the Internet, 161

U. P

A

. L. R

EV

. 1663, 1689 (2013) (‘‘One measure of a platform’s market power is the extent to

which it can engage in [privacy exploitation] without some benefit to consumers that offsets

their reduced privacy and still retain users.’’).

32

Data and Privacy Hearing at 60 (statement of Jason Furman, Prof. of the Prac. of Econ.

Pol’y, Harvard Kennedy Sch.); Data and Privacy Hearing at 54–55 (statement of Tommaso

Valletti, Prof. of Econ., Imperial Coll. Bus. Sch.)

33

D

IG

. C

OMPETITION

E

XPERT

P

ANEL

, U

NLOCKING

D

IGITAL

C

OMPETITION

43 (2019) (‘‘[T]he mis-

use of consumer data and harm to privacy is arguably an indicator of low quality caused by

a lack of competition.’’) [hereinafter Dig. Competition Expert Panel Report]; Dina Srinivasan,

The Antitrust Case Against Facebook: A Monopolist’s Journey Towards Pervasive Surveillance

in Spite of Consumers’ Preference for Privacy, 16 B

ERKELEY

B

US

. L.J. 39, 88 (2019) (‘‘Consumers

effectively face a singular choice—use Facebook and submit to the quality and stipulations of

Facebook’s product or forgo all use of the only social network.’’).

ture capitalists, for example, report that there is an innovation ‘‘kill

zone’’ that insulates dominant platforms from competitive pressure

simply because investors do not view new entrants as worthwhile

investments.

28

Other investors have said that they avoid funding

entrepreneurs and other companies that compete directly or indi-

rectly with dominant firms in the digital economy.

29

In an inter-

view with the Subcommittee, a prominent venture capital investor

explained that due to these factors, there is a strong economic in-

centive for other firms to avoid head-on competition with dominant

firms.

30

Additionally, in the absence of adequate privacy guardrails in the

United States, the persistent collection and misuse of consumer

data is an indicator of market power online.

31

Online platforms

rarely charge consumers a monetary price—products appear to be

‘‘free’’ but are monetized through people’s attention or with their

data.

32

In the absence of genuine competitive threats, dominant

firms offer fewer privacy protections than they otherwise would,

and the quality of these services has deteriorated over time. As a

result, consumers are forced to either use a service with poor pri-

vacy safeguards or forgo the service altogether.

33

Finally, the market power of the dominant platforms risks un-

dermining both political and economic liberties. The Subcommittee

encountered a prevalence of fear among market participants that

depend on the dominant platforms, many of whom expressed

unease that the success of their business and their economic liveli-

hood depend on what they viewed as the platforms’ unaccountable

and arbitrary power. Additionally, courts and enforcers have found

the dominant platforms to engage in recidivism, repeatedly vio-

lating laws and court orders. This pattern of behavior raises ques-

tions about whether these firms view themselves as above the law,

or whether they simply treat lawbreaking as a cost of business.

Lastly, the growth in the platforms’ market power has coincided

with an increase in their influence over the policymaking process.

Through a combination of direct lobbying and funding think tanks

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00018 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

13

34

Hon. David N. Cicilline, Chair, Subcomm. on Antitrust, Commercial and Admin. Law of

the H. Comm. on the Judiciary, Keynote Address at American Antitrust Institute’s 20th Annual

Policy Conference (June 20, 2019), https://cicilline.house.gov/press-release/cicilline-delivers-

keynote-address-american-antitrust-institute%E2%80%99s-20th-annual-policy.

and academics, the dominant platforms have expanded their sphere

of influence, further shaping how they are governed and regulated.

3. Recommendations

As part of the investigation of competition in digital markets, the

Subcommittee conducted a thorough examination of the adequacy

of current laws and enforcement levels. This included receiving

submissions from experts on antitrust and competition policy who

were selected on a careful, bipartisan basis to ensure the represen-

tation of a diverse range of views on these matters. The Sub-

committee also received other submissions from leading experts—

including Executive Vice President Margrethe Vestager of the Eu-

ropean Commission and Chair Rod Sims of the Australian Com-

petition and Consumer Commission—to inform this inquiry. Most

recently, on October 1, 2020, the Subcommittee held an oversight

hearing on ‘‘Proposals to Strengthen the Antitrust Laws and Re-

store Competition Online’’ to examine potential solutions to con-

cerns identified during the investigation to further inform the Re-

port’s recommendations.

Based on this oversight activity, Subcommittee Chair Cicilline re-

quested that staff provide a menu of reforms to Members of the

Subcommittee for purposes of potential legislative activity during

the remainder of the 116th Congress and thereafter. As he noted

in remarks to the American Antitrust Institute in June 2019:

[I]t is Congress’ responsibility to conduct oversight of our antitrust laws and

competition system to ensure that they are properly working and to enact

changes when they are not. While I do not have any preconceived ideas about

what the right answer is, as Chair of the Antitrust Subcommittee, I intend to

carry out that responsibility with the sense of urgency and serious deliberation

that it demands.

34

In response to this request, the Subcommittee identified a broad

set of reforms for further examination by the Members of the Sub-

committee for purposes of crafting legislative responses to the find-

ings of this Report. These reforms include proposals to: (1) address

anticompetitive conduct in digital markets; (2) strengthen merger

and monopolization enforcement; and (3) improve the sound admin-

istration of the antitrust laws through other reforms. We intend

these recommendations to serve as a complement to vigorous anti-

trust enforcement. Consistent with the views expressed by Chair

Nadler and Subcommittee Chair Cicilline in the Foreword to this

Report, we view these recommendations as complements, and not

substitutes, to forceful antitrust enforcement.

For ease of reference, these recommendations for further exam-

ination are summarized below.

(a) Restoring Competition in the Digital Economy

• Structural separations and prohibitions of certain dominant platforms from op-

erating in adjacent lines of business;

• Nondiscrimination requirements, prohibiting dominant platforms from engag-

ing in self-preferencing, and requiring them to offer equal terms for equal

products and services;

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00019 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

14

35

In 2015, Google reorganized under a new name and parent company, Alphabet, separated

various businesses, and placed Sundar Pichai as chief executive of Google. Larry Page, Chief

Executive of Google, became head of Alphabet with Sergey Brin. See Conor Dougherty, Google

to Reorganize as Alphabet to Keep Its Lead as an Innovator, N.Y. T

IMES

(Aug. 10, 2015), https://

www.nytimes.com/2015/08/11/technology/google-alphabet-restructuring.html.

• Interoperability and data portability, requiring dominant platforms to make

their services compatible with various networks and to make content and in-

formation easily portable between them;

• Presumptive prohibition against future mergers and acquisitions by the domi-

nant platforms;

• Safe harbor for news publishers in order to safeguard a free and diverse press;

and

• Prohibitions on abuses of superior bargaining power, proscribing dominant

platforms from engaging in contracting practices that derive from their domi-

nant market position, and requirement of due process protections for individ-

uals and businesses dependent on the dominant platforms.

(b) Strengthening the Antitrust Laws

• Reasserting the anti-monopoly goals of the antitrust laws and their centrality

to ensuring a healthy and vibrant democracy;

• Strengthening Section 7 of the Clayton Act, including through restoring pre-

sumptions and bright-line rules, restoring the incipiency standard and pro-

tecting nascent competitors, and strengthening the law on vertical mergers;

• Strengthening Section 2 of the Sherman Act, including by introducing a prohi-

bition on abuse of dominance and clarifying prohibitions on monopoly

leveraging, predatory pricing, denial of essential facilities, refusals to deal,

tying, and anticompetitive self-preferencing and product design; and

• Taking additional measures to strengthen overall enforcement, including

through overriding problematic precedents in the case law.

(c) Reviving Antitrust Enforcement

• Restoring robust congressional oversight of the antitrust laws and their en-

forcement;

• Restoring the federal antitrust agencies to full strength, by triggering civil

penalties and other relief for ‘‘unfair methods of competition’’ rules, requiring

the Federal Trade Commission to engage in regular data collection on con-

centration, enhancing public transparency and accountability of the agencies,

requiring regular merger retrospectives, codifying stricter prohibitions on the

revolving door, and increasing the budgets of the FTC and the Antitrust Divi-

sion of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ); and

• Strengthening private enforcement through elimination of obstacles such as

forced arbitration clauses, limits on class action formation, judicially created

standards constraining what constitutes an antitrust injury, and unduly high

pleading standards.

II. THE INVESTIGATION OF

COMPETITION IN DIGITAL MARKETS

A. Requests for Information and Submissions

1. First-Party Requests for Information

On September 13, 2019, the Committee sent bipartisan requests

for information (RFIs) to each of the four investigated platforms:

Alphabet,

35

Amazon, Apple, and Facebook. For each company, the

RFI asked for a comprehensive set of information about each of the

company’s products and services. In addition, the RFI asked the

company to submit communications among high-level executives

relating to various potentially anticompetitive acquisitions and con-

duct. The Committee requested that the platforms respond to the

RFIs by October 14, 2019.

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00020 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

15

36

Letter from Hon. Jerrold Nadler, Chair, H. Comm. on the Judiciary, Hon. Doug Collins,

Ranking Member, H. Comm on the Judiciary, Hon. David N. Cicilline, Chair, Subcomm. on Anti-

trust, Commercial and Admin. Law of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary & Hon. F. James Sensen-

brenner, Ranking Member, Subcomm. on Antitrust, Commercial and Admin. Law of the H.

Comm. on the Judiciary to Larry Page, CEO, Alphabet Inc. (Sept. 13, 2019) [hereinafter Com-

mittee Request for Information, Alphabet], https://judiciary.house.gov/sites/democrats

.judiciary.house.gov/files/documents/alphabet%20inc.%20rfi%20-%20signed%20(003).pdf.

37

Id. at 1–4.

38

The Alphabet RFI defines the term ‘‘Relevant Executives’’ as Larry Page, Sergey Brin, Ruth

Porat, David Drummond, Eric Schmidt, Sundar Pichai, Susan Wojcicki, Philipp Schindler,

Prabhakar Raghavan, Thomas Kurian, Hiroshi Lockheimer, Rishi Chandra, Keith Enright, and

Kent Walker. See id. at 4.

39

Id. at 4–9.

40

Letter from Hon. Jerrold Nadler, Chair, H. Comm. on the Judiciary, Hon. Doug Collins,

Ranking Member, H. Comm on the Judiciary, Hon. David N. Cicilline, Chair, Subcomm. on Anti-

trust, Commercial and Admin. Law of the H. Comm. on the Judiciary & Hon. F. James Sensen-

brenner, Ranking Member, Subcomm. on Antitrust, Commercial and Admin. Law of the H.

Comm. on the Judiciary to Jeff Bezos, CEO, Amazon.com, Inc. (Sept. 13, 2019) [hereinafter Com-

mittee Request for Information, Amazon], https://judiciary.house.gov/sites/democrats

.judiciary.house.gov/files/documents/amazon%20rfi%20-%20signed.pdf.

(a) Alphabet. The Committee’s RFI to Alphabet, the parent com-

pany of Google, asked for information necessary to understand how

the company operates and its role in the digital marketplace.

36

For

example, in Request A, the RFI asked for detailed financial state-

ments and a description of Alphabet’s relevant products and serv-

ices, including Google Ads, Google Search, YouTube, and Waze. In

addition, the RFI asked for information helpful for determining

whether Alphabet has monopoly power for any of its products or

services, including for each product or service: (i) a list of Alpha-

bet’s top ten competitors; and (ii) internal or external analyses of

Alphabet’s market share relative to its competitors. Request A also

asked for copies of documents and information that Alphabet had

submitted to any U.S. or international antitrust enforcement agen-

cy for antitrust investigations that took place in any of those agen-

cies within the past decade.

37

Request B asked for all communications from high-level execu-

tives, including former CEO Larry Page and current CEO Sundar

Pichai, relating to a number of Alphabet’s key acquisitions and po-

tentially anticompetitive conduct, most of which have been widely

reported in the news.

38

The RFI asked for communications, includ-

ing, but not limited to, discussions relating to the deal rationale

and any competitive threat posed by the acquired company for the

following acquisitions: Google/Android in 2005, Google/YouTube in

2006, Google/DoubleClick in 2007, Google/AdMob in 2009, and

Google’s acquisition of a minority stake in Vevo in 2013. Request B

of the Alphabet RFI also requested executive communications relat-

ing to certain categories of potential anticompetitive conduct.

39

In response to this request, Alphabet produced 1,135,398 docu-

ments, including strategy memoranda, presentations, and mate-

rials produced in prior investigations. Although Google produced a

significant amount of material, the Subcommittee did not view this

volume as a proxy for quality.

(b) Amazon. The Committee’s RFI to Amazon asked for similar

types of information helpful for understanding the competitive dy-

namics of the digital marketplace and the company’s role.

40

For ex-

ample, in Request A, the RFI asked for detailed financial state-

ments and a description of Amazon’s relevant products and serv-

ices, including Alexa, Amazon Marketplace, Amazon Prime, and

Amazon Web Services (AWS). In addition, the RFI asked for infor-

VerDate Sep 11 2014 03:38 Jul 02, 2022 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00021 Fmt 6633 Sfmt 6633 C:\HSE JACKETS\47832.TXT FRAN

JDEMLAPTOP22 with LOCATORS

16

41

Id. at 1–3.

42

The Amazon RFI defines the term ‘‘Relevant Executives’’ as Jeff Bezos, Jeff Wilke, Andy

Jassy, Jeff Blackburn, Dave Limp, Brian Olsavsky, David Zapolsky, and Jay Carney. See id.

at 3.

43

Amazon acquired ‘‘Quidsi, the e-commerce company that runs Diapers.com’’ in 2010. Claire

Cain Miller, Amazon Has a Reported Deal to Buy Parent of Diapers.com, N.Y. T

IMES

(Nov. 7,

2010), https://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/08/technology/08amazon.html.

44

Committee Request for Information, Amazon at 3–7.

45

Letter from Hon. Jerrold Nadler, Chair, H. Comm. on the Judiciary, Hon. Doug Collins,

Ranking Member, H. Comm on the Judiciary, Hon. David N. Cicilline, Chair, Subcomm. on Anti-

trust, Commercial and Admin. Law of the H.Comm. on the Judiciary & Hon. F. James Sensen-

brenner, Ranking Member, Subcomm. on Antitrust, Commercial and Admin. Law of the

H. Comm. on the Judiciary to Tim Cook, CEO, Apple, Inc. (Sept. 13, 2019) [hereinafter Com-

mittee Request for Information, Apple], https://judiciary.house.gov/sites/democrats.judiciary

.house.gov/files/documents/apple%20rfi%20-%20signed.pdf.

46